Preface

The Greater Bay Area (GBA) is an initiative by Beijing to create a world-class competitive cluster of cities with a wide range of capabilities. The GBA consists of nine cities in the Pearl River Delta Region in China’s Guangdong province plus two Special Administrative Regions (SAR) – Hong Kong and Macao. If it were a country, by population (71.2 million) it would be the 20th largest country in the world, ahead of Thailand. Its GDP of US$1.6 trillion would rank it as the 12th largest economy in the world, ahead of Russia.1

When the latest version of the GBA’s development plan was announced in February earlier this year, it seemed to be gaining momentum and all signs were indicating that it was making much progress towards its goals. However, the recent unrest in Hong Kong (since June 2019) has begun to cast doubts in some people’s minds on the prospects of the plan’s efficient and effective implementation.

In this Viewpoint, we attempt to address the related issues and present our views on the realities, opportunities and challenges that the GBA plans imply. We believe this region’s development has major implications for businesses (and people), not only with respect to the region per se, but also in that it provides a glimpse into China’s strategy of developing clusters of multiple cities. With their respective ranges of capabilities and positioning, cities in different clusters will compete against each other and also collaborate, offering diversified impacts. If successfully implemented, we believe this will be a major factor that would propel China’s overall competitiveness forward.

What Is the GBA and Why Was It Formed?

The concept of regional clusters of cities began in the 1990’s when this region was referred to as “Pearl River Delta (PRD)”. This area was, of course, where China’s reform and opening began some four decades ago when Shenzhen was designated as the first “special economic zone” where social and economic experiments were allowed to take place. Because of its proximity to Hong Kong and Macao, an overwhelmingly large part of the first generation of “overseas investors” came from these then foreign colonies. They built factories in the PRD and engaged in labor-intensive manufacturing industries. Today, the GBA has metamorphosed into a diverse region with various characteristics encompassing industry focus, technological advancement and economic development.

Geographically, eight cities are right at or adjacent to the Pearl River and its main tributaries (Hong Kong, Macao, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Foshan, Zhongshan and Zhuhai), while three are in the surrounding areas (Huizhou, Zhaoxing and Jiangmen) (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1

Map of the Greater Bay Area

Source: Outline of Development Plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau of Hong Kong), Gao Feng analysis

The GBA is a critical part of China’s overall development strategies, including continued reform and opening of China’s economy, advancements in technology and innovation and prioritization of sustainable development. The plan will also play an important role in driving the socio-economic transformation of this region, by creating a test bed for pioneering transformations, promoting a higher-utility society and sustainability and supporting the development of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

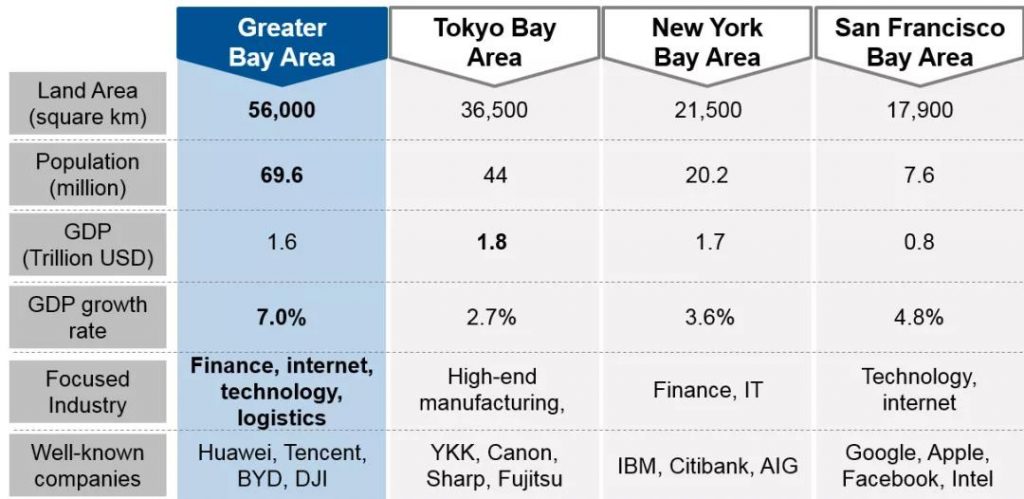

The Chinese like to draw comparisons of what they do with what they see in the rest of the world. In this case, they are comparing the GBA with “the world’s largest ‘bay areas’” such as the New York Bay Area, Tokyo Bay Area and San Francisco Bay Area and suggest that the GBA will rival these “traditional bay areas” through greater diversity in activities. According to this analysis, the other three bay areas have focused on development in one or two areas while comparatively, the GBA is developing in many diverse areas simultaneously, mainly finance, internet, technology and logistics (see Exhibit 2). In 2018, the GBA’s total GDP had reached US$1.6 trillion and this is expected to increase to US$7.4 trillion by 2030, which would make it the world’s top bay area in terms of GDP.

In terms of innovation and technology, the Shenzhen-Hong Kong technology cluster was ranked the world’s second most innovative cluster in the Global Innovation Index 2018.2 Shenzhen, the leading technology hub in China, is currently home to more than three million businesses.3 Its investment in R&D is one of the world’s highest with more than US$14.9 billion invested in 2018 alone. Dongguan, a city to the north of Shenzhen, is a center for manufacturing, home to about 9,000 foreign invested industrial enterprises.4 It aims to be home to a cluster of globally competitive companies in high-end manufacturing.

Guangzhou, the capital and most populous city of Guangdong province, is an international business trade center and an integrated transportation hub. Macao plans on leveraging its role as a tourism and leisure hub to develop in areas such as gaming equipment and security services for helping establish GBA as a tourism destination. According to the latest budget plans, the government of Hong Kong, which traditionally has not put much focus on technology and innovation, has pledged to invest more than US$5 billion in the technology sector. The SAR’s R&D expenditure is expected to double in five years.5

The GBA is already home to many well-known companies, such as Huawei, Tencent, Ping An and BYD. With annual revenue exceeding US$100 billion, Huawei is now a leading global player in telecommunications equipment and smart devices. Internet giant Tencent is one of the world’s ten most valuable companies. Ping An was ranked the world’s most valuable insurance brand in 2019 by brand valuation consultancy Brand Finance6 and has been rapidly expanding beyond traditional financial services into areas such as fintech and healthcare. Carmaker BYD has become a leader in new energy-related innovations, including batteries, electric vehicles, solar energy and energy storage.

The GBA is also home to many of China’s most promising tech start-ups. On the Hurun Global Unicorn List 20197 (unicorn refers to unlisted companies with a valuation of at least US$1 billion), top GBA-headquartered unicorns include WeBank (one of the leading digital banks in the world), drone manufacturer DJI (who dominates the global consumer-class drone market with a 74% market share8), Royole (manufacturer of flexible displays, flexible sensors and smart devices) and UBTech (a robotics company recently valued at $5 billion).

Exhibit 2

Key Indicators of the Four Major Bay Areas (2017)

Source:36Kr.com, South China Morning Post, Gao Feng analysis

Innovation and Entrepreneurship Reshaping China

Many observers have asserted for long that China was a state economy and that its central government dictated what the rest of the country would do. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) used to overwhelmingly dominate China’s economy but that is no longer the case today. China was widely known as a “copycat nation” because of the widespread perception of infringement of intellectual property. However, that image has started fading since over a decade ago when the Chinese quickly embraced technologies, especially the wireless internet, to create business innovations that have fundamentally changed Chinese society in many ways. These innovations have overwhelmingly been driven by private-owned enterprises (POEs). According to the Evergrande Research Institute,9 Chinese POEs have achieved an admirable feat as described with the “456789” notion (using around 40% of the country’s bank loans, contributing more than 50% of tax revenue, producing more than 60% of GDP, accounting for more than 70% of industrial upgrades and innovation, providing more than 80% of urban employment and owning more than 90% of enterprises).

In fact, relentless experimentation over the course of more than four decades of reform and opening has resulted in development and evolution of China’s unique economic model into what we call a “three-layered duality”. At the top, the central government has set the country’s overarching strategy of developing into a technologically advanced and innovative society. At the grass-roots level, private sector entrepreneurs have re-emerged (since the end of the Cultural Revolution) and become a major force driving the country’s economic growth. And in the middle, China’s local governments channel their resources to push national and local priorities, often in close collaboration with entrepreneurs. Leading local governments provide funding and incubation infrastructure to start-ups. While often competing with each other to optimize the utility of innovation to people living in their jurisdictions, some local governments also cooperate with enterprises in regional clusters. The GBA is a prime example of this kind of cluster collaboration approach.

China has long moved beyond having SOEs as the only dominant part of its economic structure to a dual structure comprising of both SOEs and POEs. While there were – and are – glitches between these two types of enterprises, they have also developed a symbiotic relationship. SOEs take on initiatives related to the country’s mission-critical projects, such as the high-speed railway network which was built from virtually nothing to the world’s most extensive system over slightly more than a decade. Meanwhile, as mentioned, POEs led by China’s entrepreneurs have become the main drivers of market-driven innovations, often enabled by technologies such as the wireless internet.

Today, internet giants Alibaba and Tencent rank among the ten most valuable companies in the world. Other tech companies such as Meituan Dianping, Ant Financial, ByteDance, Didi Chuxing, Pinduoduo, JD.com and Xiaomi are all fast growing and have become the next pack of “exponential organizations” together with other tech incumbents, Baidu and NetEase. Most importantly, entrepreneurship has become the very fabric of the Chinese culture in which entrepreneurs are often young (many are “post 90s”); they are present not only in innovative hubs such as Shenzhen or Beijing’s Zhongguancun, but also across many parts of China. Perhaps most importantly, as a society, China has accepted failure in entrepreneurial pursuit as a part of life. This is a sea change in China. According to the Hurun Global Unicorn List 2019, China now leads the world with the largest number of unicorns at 206, followed by the US at 203.

China’s innovation is manifesting across a wide range of sectors, from more traditional sectors such as consumer and home products/electronics, to newer sectors such as “new retail”, “big health”, new energy vehicles and mobility-as-a-service.* With major emerging disruptive technologies, such as Internet of Things (IoT), 5G connectivity, cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain thriving at the same time in the world’s largest digital economy, and a data privacy regime that is more relaxed compared to that in the West, China is at the cusp of entering another tech innovation era that probably will be of a larger scale and have a longer duration than the wireless internet era.

Dimensioning the GBA’s Future

Against the above backdrop, what can we expect from the GBA? We believe several key dimensions will drive the future of the GBA. They are mobility, connectivity, digital lifestyle, smart infrastructure and internationalization (Exhibit 3). What we describe below is our interpretation of the future vision of the GBA plan, formulated before the start of the unrest in Hong Kong.

Exhibit 3

Several Dimensions of the GBA’s Future

Source: Gao Feng analysis

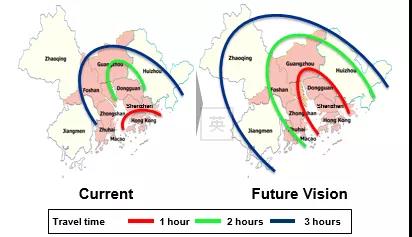

In terms of mobility, new streamlined and efficient infrastructure and ports are being put in place. Goods will travel more freely in terms of speed and customs clearance, encouraging cross-border business. People will also travel more efficiently throughout the region expanding the size of their living and working circles. This will benefit businesses through widening of the talent pool and bringing new commercial opportunities to the region (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4

Current and Future Vision of Living and Working Circles within the GBA

Source:2022 Foundation, Gao Feng analysis

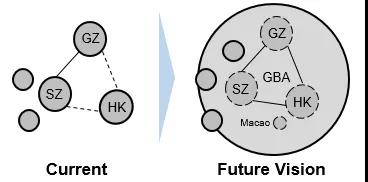

Enhanced connectivity within the GBA will imply a more convenient, effective and collaborative environment that would facilitate enhanced knowledge sharing across the region and creation of the right ecosystem and synergies amongst governments, businesses and people. Cities will be able to form complementary roles and maximize the GBA’s economic impact (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5

Current and Future Vision of Connectivity in the GBA

Note: HK = Hong Kong, GZ =Guangzhou, SZ = Shenzhen

Source: Gao Feng analysis

The growing use of a digital lifestyle will further increase market efficiency. In China, consumers demand convenience and efficiency and are highly willing to adopt new digital trends. They also build communities by sharing experiences and stories through different social media. Businesses in China too are quickly adopting digital strategies and creating new ways to interact with consumers and provide more personalized products and services. In the future, both work and life will be increasingly online and consumption of both products and services through online portals will increase. Digital platforms are enhancing efficiency and new opportunities are emerging to better fit into consumers’ digital lifestyles.

Smart infrastructure will vastly improve the work and social lifestyles of GBA’s population, embedding technologies such as AI, IoT, 5G and blockchain into the infrastructure. Real-time data acquisition and analysis shall allow cities to make more informed decisions, to plan better and to address urban challenges through smart public services. GBA cities (in particular Shenzhen and Guangzhou) are innovative and they are willing to experiment with disruptive technologies, which leads to increased opportunities for local businesses. New centers of commercial activities will spawn in more remote areas, such as lower tier cities, due to more efficient infrastructure. Logistics will become more efficient, bringing businesses closer and more reactive to consumer needs. More distributed and remote working styles will come into being and talent will be increasingly cross-border. In particular, industries building on these disruptive technologies will have significant potential due to the increasing connectivity.

Part of the plan of course involves close cooperation with Hong Kong. The Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) promulgated in 2003 was a step towards strengthening cooperation between Hong Kong and mainland China and promoting their joint development. One of the key steps in this respect is to help GBA cities internationalize through Hong Kong, since its well-respected legal system, low taxation and status as a global financial center make it a highly attractive gateway to China for foreign companies. Hong Kong and Shenzhen’s international ports also provide opportunities for businesses in the region to expand beyond their immediately accessible markets and reach international coverage.

Would Hong Kong’s Unrest Matter?

The current unrest in Hong Kong has cast uncertainties on future participation of Hong Kong in the GBA. Hong Kong’s legal and tax systems, freely convertible currency and active debt and equity markets cannot be easily replicated in mainland China (at least not in the near-term). However, while it is true that Hong Kong plays a key role in the GBA as an international center, many of the GBA’s key developments such as smart infrastructure and technology development can continue with or without participation of Hong Kong.

In August of this year, China’s State Council and the Central Committee of the Communist Party issued a new guideline outlining an ambitious plan for the future of Shenzhen. It set out plans to transform Shenzhen into a “pilot area and a leading city in the world in economic strength and quality of development, with the focus on research and development, industrial innovation, public services and ecological environment”.10 The plan calls for the city to become a “global benchmark city in its competitiveness, innovative capacity and influence” by mid-century. A new pilot program was also announced to ease the yuan’s convertibility in Shenzhen.11 Meanwhile, Macao has also been investigating the possibility of becoming an offshore yuan trading center and has submitted a proposal to create an offshore yuan-based stock exchange to the central government.12 This would provide another channel for GBA companies to raise capital.

Of course, Hong Kong’s financial industry and infrastructure are much more mature and sophisticated than the rest of the GBA. But are the plans in Shenzhen and Macao a signal of China preparing contingency plans for the longer run?

What Does It All Mean?

The GBA still faces some challenges and will continue to face some governance structural barriers such as legal systems, fluctuations in exchange rates and physical movement across borders. One difficulty that companies face would be protection for intellectual property rights (this is a focus point in the current Sino-US trade negotiations). This is one area where Hong Kong has in the past, been able to attract investment from foreign companies looking to enter China. There are also local-level challenges that need to be addressed in different areas, such as the differences in education systems, public transportation network and right of abode which make things difficult for people who work or travel between the regions (although a number of infrastructure projects such as the Zhongshan-Shenzhen bridge are in full steam and will make travel between cities increasingly easy).

The GBA will likely offer good opportunities for investments in key areas or industries such as AI, blockchain and IoT. More key players will likely emerge in the region and this will represent increased competitiveness of companies in the GBA as they go global. For companies not based in the GBA, partnerships with GBA companies and/or working with their ecosystems could be beneficial, especially as GBA companies are going international.

Many companies in the GBA will leverage the government’s policies and priorities to decide the areas of their focus. They will also participate in the GBA ecosystem and not just in their base or local city. There are also some upcoming industries that will face major disruptions caused by the GBA’s development, including smart infrastructure, AI and IoT. Consumer segmentation and demographics are also likely to change and expand and lifestyles will become more digitalized, personalized and ubiquitous. Business solutions will need to be designed to face cross-border competition.

The GBA constitutes an opportunity for Hong Kong to be more closely involved in China’s development. While Hong Kong is important to the GBA’s future, the reverse is also true. Participating in the GBA ecosystem will bring new opportunities for Hong Kong companies, especially in the context of new innovative business models and solutions that need to be created to adapt to Chinese consumers’ demands and the rapidly changing environment. When new demand patterns are emerging in the market, companies should learn to embrace co-opetition through partnerships with competitors or players from adjacent industries to build capabilities and capture opportunities.

The GBA represents many new opportunities in the future for businesses, both local and global. At the same time, companies operating in the region will also face challenges, especially due to the ever-changing nature of the business environment and policies. Companies that can seize these opportunities will be among the true winners.

Efforts to advance the GBA plan is continuing despite the unrest in Hong Kong. In early November, new policy on lifting previous restrictions on Hong Kong and Macao people buying homes in the nine mainland cities was announced. They will enjoy the same treatment as residents of the mainland cities. They will be also able to enroll their children in mainland local schools. Other policies include cross-boundary wealth management schemes and professional qualification extensions.13

Epilogue

The GBA is an ambitious plan of Beijing to create a large cluster of cities. Due to its scale and complexity, making it happen will be quite a daunting task. However, if it is successful, the impact will be huge.

Like many of Beijing’s initiatives in the last four decades of reform and opening, the plans seem large and unattainable when they are first announced. Some of the plans did not fully materialize or even ended up as a flop. However, in many cases, China was somehow able to find ways to achieve (and sometimes even over-achieve) the original goals, albeit after experiencing some ups and downs along the way. Given its past record, no one should underestimate China’s wherewithal to make the GBA happen.

In our view, the current Hong Kong unrest may cast doubts on the viability of the GBA and perhaps slow down its progress. However, over the next several months as Hong Kong’s situation begins to stabilize, rationality will prevail and the GBA’s strategic sense will present itself.

Companies, whether headquartered in mainland China or in Hong Kong or Macao (or beyond) should evaluate carefully what the GBA really means in terms of opportunities and risks. They will need a GBA strategy.

References:

1. Hong Kong Trade Development Council Research (2019, June 18). Statistics of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Hktdc.com. Retrieved October 25, 2019, from

http://hong-kong-economy-research.hktdc.com/business-news/article/Guangdong-Hong-Kong-Macau-Bay-Area/Statistics-of-the-Guangdong-Hong-Kong-Macao-Greater-Bay-Area/bayarea/en/1/1X000000/1X0AE3Q1.htm.

2. Cornell University, INSEAD, and World Intellectual Property Organization (2018). Global Innovation Index 2018: Energizing the World with Innovation. Wipo.net. Retrieved October 27, 2019, from https://www.wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=4330.

3. Cheung, E. (2019, April 01). “Greater Bay Area: 10 facts to put it in perspective”. Scmp.com. Retrieved October 20, 2019, from

https://www.scmp.com/native/economy/china-economy/topics/great-powerhouse/article/3002844/greater-bay-area-10-facts-put.

4. Hong Kong Trade Development Council Research (2019, May 16). Dongguan (Guangdong) City Information. Hktdc.com. Retrieved October 20, 2019, from

http://china-trade-research.hktdc.com/business-news/article/Facts-and-Figures/Dongguan-Guangdong-City-Information/ff/en/1/1X000000/1X09W31Q.htm.

5. The Development Bank of Singapore Limited (DBS Bank) (2019, March 07). DBS Focus: Hong Kong – Core of the Greater Bay Area. Dbs.com. Retrieved October 21, 2019, from

https://www.dbs.com/aics/templatedata/article/generic/data/en/GR/032019/190307_insights_hong_kong_core_of_the_greater_bay_area.xml.

6. Brand Finance (2019, May 15). Stellar brand value from Ping An moves China into pole position on global insurance stage. Brandfinance.com. Retrieved November 1, 2019, from https://brandfinance.com/news/press-releases/stellar-brand-value-from-ping-an-moves-china-into-pole-position-on-global-insurance-stage/

7. Hurun Research Institute (2019, October 21). Hurun Global Unicorn List 2019. Hurun.net. Retrieved October 21, 2019, from https://www.hurun.net/EN/Article/Details?num=A38B8285034B.

8. Skylogic Research Drone Analyst (2019, January 14). 2018 Drone Market Sector Report. Droneanalyst.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018, from

9. Evergrande Research Institute (2019, August 21). Current Living Environment and Suggestions For Private Enterprises. Baijiahao.baidu.com. Retrieved October 28, 2019, from

http://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1642445902558451559&wfr=spider&for=pc.

10. China’s State Council and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (2019, August 18). China To Build Shenzhen Into Socialist Demonstration Area. gov.cn Retrieved October 29, 2019, from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-08/18/content_5422183.htm.

11. Yiu, E. (2019, October 10). Unconvertible Yuan Is A Drag On Shenzhen’s Race To Supplant Hong Kong’s Unique Role As China’s Offshore Financial Centre. Scmp.com. Retrieved October 29, 2019, from https://www.scmp.com/business/companies/article/3032199/unconvertible-yuan-drag-shenzhens-race-supplant-hong-kongs.

12. He, H. and Ng, E. (2019, October 13). Macau Submits Proposal For ‘Offshore Yuan Nasdaq’ To Chinese Government. Scmp.com. Retrieved October 29, 2019, from

https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3032746/plans-offshore-renminbi-nasdaq-macau-submitted-beijing.

13. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (2019, November 6). Chief Executive attends meeting of Leading Group for Development of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Info.gov.hk. Retrieved November 07, 2019, from https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201911/06/P2019110600764.htm.