David Pilling | FT.com

June 24,2015

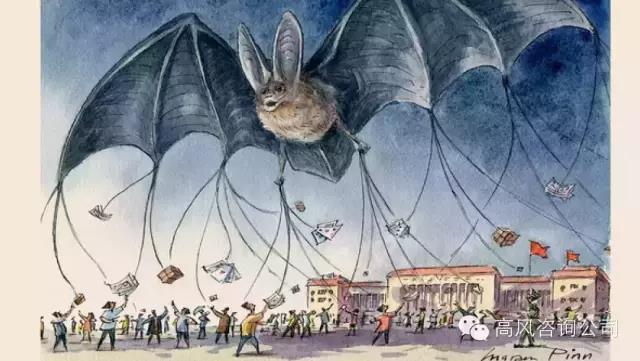

Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent are three internet groups that have turned much of China upside down here is an overarching force in China with tentacles reaching deep into almost everybody’s life. That force is not the Communist party, whose influence in people’s day-to-day affairs — though all too real — has waned and can appear almost invisible to those who do not seek to buck the system.

The more disruptive force to be reckoned with these days is epitomised by the three large internet groups: Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, collectively known as BAT, which have turned much of China upside down in just a few short years. Take the example of Ant Financial.

Last week, it completed fundraising that values the company at $45bn to $50bn. It operates Alipay, an online payments system that claims to handle nearly $800bn in e-transactions a year, three times more than PayPal, its US equivalent.

That system, an essential part of China’s financial and retail architecture, and one familiar to almost every Chinese urbanite, is no brainchild of the Communist party. Instead it was the creation of Jack Ma, the former English teacher who founded Alibaba. Mr Ma established the system a decade ago as the backbone for Taobao, his consumer-to-consumer business.

The name literally means “digging for treasure”, something that Mr Ma, one of China’s richest people, has clearly found.

Alibaba handles 80 per cent of China’s ecommerce, according to iResearch, a Beijing-based consultancy. That is a monopolistic position that even the Communist party, with its 87m members out of a population of 1.3bn, can only dream about.

True, the Communist party still regulates where people live (in the city or the countryside),what they publish (though less what they say) and how many children they have (though the one-child policy is fast fading).

China’s internet companies, on the other hand, hold ever greater sway on how people shop,invest, travel, entertain themselves and interact socially.

The BAT companies, which dominate search, ecommerce and gaming/social media, together with other upstarts, such as Xiaomi, a five-year-old company that has pioneered the $50 smartphone, are upending how people live.

When we think of the Chinese internet, we tend to think of the overweening influence of the state through censorship. Yet the internet is also a liberating force that is unleashing entrepreneurial energy, bringing market forces to bear in diverse corners of the economy and expanding the role of the private sector at the expense of entrenched state enterprises. In China’s nominally controlled economy, the private sector long ago outstripped the state as the engine of growth. According to Edward Tse, a management consultant and author of China’s Disruptors , this has resulted in the “emergence of a new group of entrepreneurial business leaders . . . most operating with little direct government influence or support, and all transforming their industries”.

Privately run businesses, he estimates, account for three-quarters of national output. By 2013, China had about 12m privately held and 42m family run businesses against 2.3m state-owned companies.

At the forefront are technology companies in general and internet companies in particular. As elsewhere, in China the online and offline worlds are colliding.

Taxi apps such as Didi Dache, backed by Alibaba and Tencent, have brought market forces to bear where prices were previously set by the state. They are threatening lucrative local taxi monopolies, provoking crackdowns and protests by drivers in several cities.

In finance, where deposit rates are state regulated, the BAT companies and others are offering savings and investment products with much better rates. Yue Bao (“leftover treasure”), a money-market fund distributed by Alibaba over Alipay, has accumulated assets of nearly Rmb600bn in less than two years. Beijing, which wants gradually to liberalise banking, is allowing this crop of private companies to catalyse change. In important respects, though, even the fiercest of China’s internet pioneers do not operate in a free market. For a start, they conduct their business behind the Great Firewall, a politically motivated barrier that has protected them from the likes of Google, Twitter and Facebook.

In practice, the BAT companies are so close to the government they often behave like quasistate-owned enterprises anyway, even to the extent that they help form regulation. The government’s ecommerce strategy, announced in March by Li Keqiang, the premier, was originally conceived by Pony Ma, chairman of Tencent.Authorities are not always sure how to regulate these powerful new companies. When the State Administration for Industry and Commerce criticised Alibaba for the prevalence of counterfeit goods sold on its websites, Jack Ma’s company threw its weight around, forcing the government regulator to retreat.

If the authorities really want to fight commercial disruption, however, they have the tools to do so. In 2014, for example, the central bank suspended “virtual” credit cards issued by Alibaba and Tencent, blocking their path into online credit.

One must assume that, if push came to shove, the authorities could cripple even the biggest private company. Yet so embedded are the likes of Alibaba and Baidu in people’s lives that even the mighty Communist party might have cause to pause.