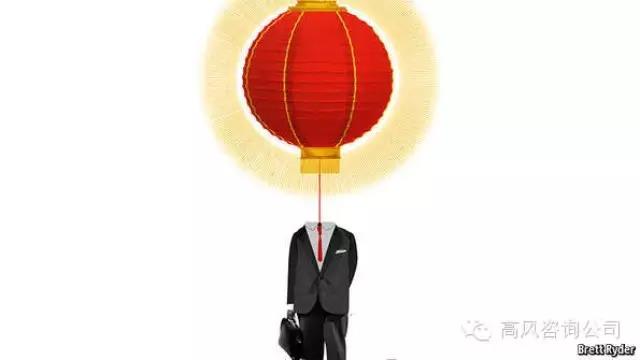

The sceptics exaggerate: in some industries Chinese firms are innovative

Jul 11th 2015 | Schumpeter

“YEAH, the Chinese can take a test,but…they’re not terribly imaginative. They’re not entrepreneurial. Theydon’t innovate—that’s why they’re stealing our intellectual property.” Sodeclared Carly Fiorina, a former boss of Hewlett-Packard, shortly beforeannouncing her candidacy for America’s presidency earlier this year. MsFiorina’s provocation fuelled a global debate over one of the big businessquestions of the age: can China innovate?

Sceptics make two arguments. They point tothe historically lax protection of intellectual-property (IP) rights and theproliferation of copycat business models in China as evidence that Chinesecompanies cannot create for themselves. An article published in MIT Sloan Management Reviewlast year claimed that Chinese theft of IP costs American firms $300 billion ayear. Nay-sayers also argue that the heavy-handed approach taken by China’sgovernment to promoting innovation is in fact retarding it.

Two new publications bang thedrum for the opposite side of this debate. “The China Effect on GlobalInnovation”, a study by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the think-tank ofthe eponymous consulting firm, argues that Chinese companies do indeed showpromise. MGI does not fall into the common trap of conflating innovation withinvention: “The proof of successful innovation is the ability of companies toexpand revenue and raise profits,” as opposed to filing lots of patents thatnever get used, or releasing a stream of novelty products that fail to generatea return. And “China’s Disruptors”, a book out on July14th, by Edward Tse, a management consultant, argues that China’s dynamicprivate sector has risen with the help of, not despite, government policies oninnovation.

The MGI team scrutinised financial data on20,000 firms from China and elsewhere, to see if they create value forcustomers and shareholders. It weighed up the extent to which they do sothrough such things as basic research, by throwing large numbers of engineersat problems (as firms like Huawei, a telecoms-equipment maker, are good atdoing), by improving manufacturing processes, and so on. China has spent years,and large sums of money, trying to be an “innovation sponge” that absorbs foreigntechnologies. Despite this, notes the MGI report, it still lags the West increating world-class medicines, civil aircraft and cars.

However, it finds that in many othersectors, China is now taking a global lead in two areas of innovation: inimproving consumer products and the business models used to sell them; and inmaking manufacturing processes cheaper, quicker and better. As a result,Chinese firms now outsell foreign rivals in such things as householdappliances, internet software and consumer electronics. They are helped by thefact that their home market is so huge. But they are also fleet of foot.Chinese consumers are ready adopters of smartphones, social media ande-commerce, as well as being value-conscious and brand-licentious. If consumer firmscan make it in China, they can make it anywhere.

Chinese firms are inventing new businessmodels. The West’s online firms generate most of their revenue fromadvertising. But China’s advertising industry is only about one-eighth the sizeof America’s, so Chinese digital firms have had to find new ways to monetisetheir users’ eyeballs. Tencent generates 90% of its revenue from online games,sales of virtual items on social platforms and e-commerce. Average revenue peruser in 2014 was $16, which was $6 more than Facebook. YY.com, an online-videoplatform, lets viewers buy electronic “roses” to shower upon video artistswhose shows they enjoyed. YY says its top performers, who get a cut of therevenue, can earn more than 20,000 yuan ($3,200) a month, seven times theaverage factory worker’s pay.

What about the other argument, on the role ofthe state? The pessimists argue that China’s bureaucrats are bad forprivate-sector innovation. In a sense Mr Tse is an unlikely person to bechallenging this view. He was the top China man for the Boston Consulting Groupand then for Booz & Company (two rival consulting outfits). His bookchronicles in compelling detail the rise of the mainland’s entrepreneurialeconomy from the ashes of Maoist policies. And yet this arch-capitalist insiststhat, “Companies alone cannot make the massive long-term commitment ofresources needed to drive innovation in many crucial areas.” Just as Americanpublic spending on universities and defence research boosted Silicon Valley’searly stars like HP, in China too, “the state has to lead the way.” He isencouraged by the fact that China now spends more than $200 billion a year onresearch and development (public and private), putting it above the EuropeanUnion as a proportion of GDP, though still behind America.

Mr Tse also points to evidence that, he argues,shows how China’s regulatory and legal infrastructure is becoming more“innovation-friendly”. Baidu, China’s biggest internet-search firm, used to benotorious for hosting pirated music and videos. Thanks to regulatory crackdownsand legal challenges from rights holders, it has cleaned up its act and hasbecome a big, legitimate distributor of foreign TV shows.

Setting the stage

Ms Fiorina is right that most Chinese firmsare not at the cutting-edge of technology, but she is wrong to say they areincapable of value-creating innovation. HP itself has been overtaken by Lenovoof China as the world’s leading computer-maker, helped not just by its boldacquisitions of Western businesses but by its impressive in-house productdevelopment. And Mr Tse is right that there is a role forgovernment in setting the stage for innovation. However, in civil aviation and carmaking, the governmentis also dictating the structure of the industry: in planes, through astate-owned national champion, AVIC; and in cars, via forced partnerships withforeign firms. Chinese firms can innovate. But its government has not yetlearned to distinguish between helpful support and counter-productive meddling.