Updated July 15 2015 丨 Policy Innovations

By Edward Tse

(Reprinted fromChina’s Disruptors: How Alibaba, Xiaomi, Tencent, and Other Companies Are Changing the Rules of Businessby Edward Tse with permission of Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright (c) Edward Tse, 2015.)

Since the early 1990s, China has consistently been the world’s fastest-growing economy. It has opened its economy and its population to the outside world with a speed and success that is unprecedented not just for China but for any country. In the process, China has also acquired a large number of critics, especially in the United States. These include politicians, among them members of the Obama administration and other key figures in both the Republican and Democratic parties; leading economists such as Nobel prize winner Paul Krugman and Peter Navarro of the University of California, Irvine; and analysts such as Gordon Chang, author of the 2001 book The Coming Collapse of China. These critics argue that China’s economic success is due, in good part, to unfair practices by the Chinese government: its mercantilist trade regime, its currency manipulation that keeps the value of the yuan artificially low, its high-pressure efforts to open external markets to its businesses, its subsidies for manufacturers, and its widespread pirating of foreign goods and technology. The main beneficiaries of these policies, they say, have been Chinese export manufacturers—those who produce inexpensive smartphones, computers, toys, clothes, and other consumer goods, sucking in jobs from the rest of the world and dumping their products into Europe and America to drive competitors out of business.

Another factor frequently cited by overseas critics is the prevalence and influence of state-owned enterprises in China. The country’s biggest companies—its banks and insurers, oil and energy companies, telecom operators and airlines, leading steel, auto, and construction firms—are all government-owned or government-controlled. The Chinese members of the Fortune Global 500, which ranks the world’s top companies by revenue, would seem to confirm this view. In mid-2014, some 92 companies on the list were Chinese, but just 10 of these were privately owned enterprises. Using money from China’s $4 trillion of foreign exchange reserves, many of these businesses have been investing heavily overseas—been “buying the world,” as various book titles and headlines have suggested. Since the early 2000s, Chinese state-owned firms, backed by state-owned banks, have been striking multibillion-dollar deals in Africa, South America, and other regions, gaining access to energy supplies, raw materials, and even land for farming. Wherever these companies have gone, Chinese construction firms, also state-owned, have accompanied them, building ports, roads, and other infrastructure both to make sure that goods can be shipped back to China and to support the development of their host nations. But this view of the Chinese economy as a mercantile juggernaut, driven by a single-minded government, does not tell the most dramatic part of the Chinese story, the part with the greatest potential impact on the rest of the world.

That is the emergence of a new group of entrepreneurial business leaders, all from the private sector, most of them operating with little direct government influence or support, and all of them transforming their industries. These entrepreneurial disruptors are among the most successful and powerful individuals in China today. Many are billionaires, and some are multibillionaires. They are the reason that (as of August 2014) China hosts the world’s second-largest concentration of billionaires after the United States—152 out of the total 1,645, according to Forbes magazine.

The rise of these disruptive entrepreneurs is all the more noteworthy because, at the time of Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, China had no private businesses. All of the country’s industry and agriculture was publicly owned, run either by the central government, by local governments, or through collectives. Today, thanks to the economic reforms of the last 35 years, the private sector accounts for at least three-quarters of China’s economic output.

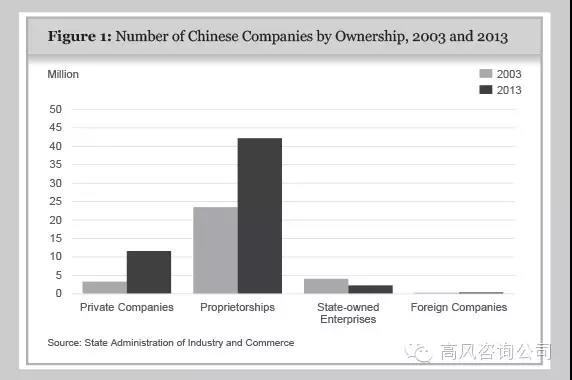

The Chinese government, despite having long since abandoned central planning, continues to regard itself as playing a key role in managing the overall direction of the Chinese economy. China remains home to approximately 2.3 million state-owned companies. That number, however, is dwarfed by its other businesses. As early as 2004, China had about 3.3 million privately held companies—many owned by investors with shares traded on public exchanges—and 24 million proprietorships—individually or family-run operations. By 2013, the country had nearly 12 million private companies and more than 42 million proprietorships (see Figure 1). Moreover, the government is firmly committed to increasing these totals. In the first seven months of 2014, thanks to regulatory reforms abolishing registered capital requirements, 1.5 million new private companies were set up—double the number during the same period the year before.

The number of state-owned companies, meanwhile, has fallen by almost half since 2004. And though these companies are far more productive than they were a decade ago, their increase in output is a fraction of that of the private sector. In 2000, total revenues earned by state-owned and non-state-owned industrial companies were roughly the same, at about 4 trillion yuan each. By 2013, while total revenues at state-owned companies had risen just over sixfold, those in the non-state sector had risen more than 18 times (see Figure 2). Profits jumped even more over the same period, up nearly seven times for state-owned companies, but up nearly 23‑fold for non-state ones.

The Chinese entrepreneurs have thrived, in part, because they created companies able to change as China changed. Many of them first set up businesses when the economy was still dominated by the state, which set most prices and appointed most company leaders. They survived the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s. They fought off competition from the flood of foreign companies that arrived after China entered the World Trade Organization in the 2000s. And they rode out the worldwide downturn that followed the global financial crisis during the late 2000s and early 2010s. Throughout all of this, China’s entrepreneurs created an economy largely outside the direct control of the government. They are answerable primarily to the customers who consume the products and services their companies offer. As with their counterparts around the world, they are typically energetic, imaginative, and often idiosyncratic. They are extraordinary individuals in their own right, especially when you consider that they have created successful businesses with little official backing within a traditionally risk-averse culture that reveres authority and conformity.

These entrepreneurs come in all forms imaginable. They are old and young; some with no formal education beyond high school, others with doctorates; some from China’s richest and largest cities, others from remote country towns. Most, of course, run small companies, but others lead industry giants that employ tens of thousands of people. Some are highly influential, with access to the highest ranks of government. Others suffer from sustained official prejudice that favors state-owned firms, a factor that can make matters of everyday business, such as securing a bank loan, a nightmare.

Many of today’s most successful Chinese entrepreneurs, most of them now in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, had no experience in business when they started their companies. They had to learn things as they went along through a continual process of trial and error. They were “crossing the river by feeling the stones,” as Deng Xiaoping, China’s paramount leader from 1978 to 1998, characterized his approach to economic reform.

Among those who started businesses in the period from the 1980s through the early 2000s, not one could have foreseen the China of 2014. Yet these are the people who have played the single biggest role in creating the wealth that exists in China today. Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow at Washington, DC-based Peterson Institute for International Economics and one of the world’s leading academic experts on the Chinese economy, estimates that privately controlled companies now account for two-thirds of all urban employment—meaning that almost all of the growth in urban employment since 1978 can be attributed to the private sector.

Chinese entrepreneurs are sometimes compared to the Russian oligarchs of the early 2000s. But the oligarchs built their fortunes by taking advantage of the privatization of industry that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, often using their connections and positions to amass huge holdings in resource companies. The Chinese entrepreneurs we’re looking at in this book, in contrast, have almost all developed their businesses from the ground up, in many instances starting from an apartment or a market stall, or raising a few thousand dollars from friends and relatives. They built their companies by meeting the needs of their customers, often in businesses that no one else saw as feasible.

These business leaders know that they are riding and contributing to a historic wave of economic activity. As creators of the fastest-growing enterprises in the fastest-growing economy in the world, they recognize that they have immense potential influence. Running companies that have grown even faster than the Chinese economy, they are establishing the rules that all companies in China will have to follow. Despite having had almost no formal business training, they are moving rapidly to compete with the same companies from whom they were drawing inspiration just a few years ago, both in China and internationally. In the process, they will rewrite the rules of global management.