Edward Tse and Sunny Cheng say after years of inaction, Hong Kong must create new jobs for young people to give them the skills they need to become our future business leaders

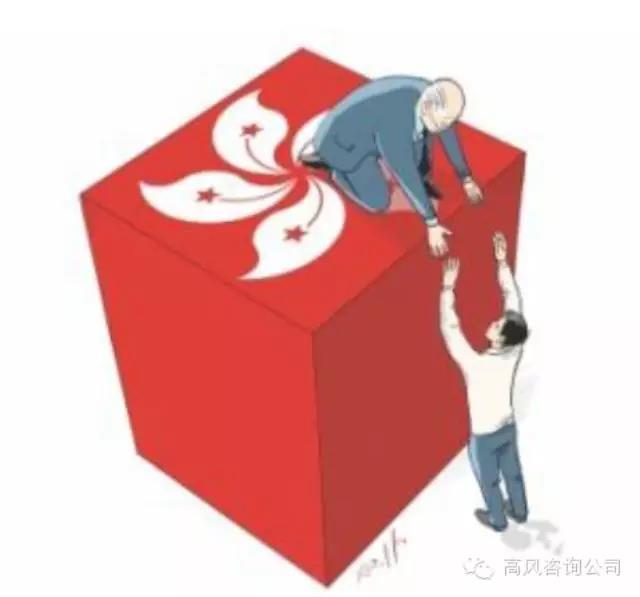

The underlying assumption for social mobility to exist is that there is room above, so that younger workers can indeed move up. But, in a stagnant economy, where there is no room above, the only way to break the social mobility deadlock is to create new industries, and thus new jobs and mobility.

In the United States today, employment growth is mainly driven by the technology sector. For cities with little hi-tech industry, people simply move to seek work elsewhere. In Spain, Portugal and Greece, where youth employment is a problem, we are seeing more frustration and unrest. In Glasgow, where youth unemployment is among the highest in Scotland, the city voted for independence in the Scottish referendum. The young are saying: if there is no future for us, then we want change.

Each year, Hong Kong has about 70,000 school-leavers. They become qualified to vote at the same time. We must create new jobs for them – not low-wage opportunities but those where they can develop their skills and become future business leaders in another 10 to 15 years.

Since the handover, Hong Kong’s government has failed to seriously address this issue. The strategy so far has been to continue on the same track: favouring incumbent big businesses; encouraging mainland tourism; propping up the property market and fortifying our place as a financial centre. Yet jobs in tourism and retail are often low paying, without real upward mobility. In property, the money goes to the developers, who share little of the wealth. In finance, the best jobs are going to mainlanders and expatriates.

Meanwhile, we have seen the demise of our manufacturing sector, and the trading sector has declined rapidly. Fifteen years of policy neglect has created more than a million frustrated, if not angry, voters. Also, Hong Kong’s economy is losing its diversity and, therefore, its resilience. Worse, what used to be the bedrock of Hong Kong, our entrepreneurial spirit, has now dampened beyond recognition.

In the past, upward mobility was not an issue. Legends, such as Li Ka-shing and Lee Shau-kee, began with nothing. Success stories abounded as young people worked their way into senior positions at corporations, including multinationals.

Yet in the past 15 to 20 years, Hong Kong has had no new, self-made tycoon. The Hong Kong delegation of business leaders recently received by President Xi Jinping had an average age of over 70 – a strong signal for change.

In contrast, entrepreneurship in China has been thriving, especially in the past decade. Waves of entrepreneurs have emerged, from a wide range of industries, such as the internet, food, autos, renewable energy, logistics, retail, telecoms and property; many since the 1980s – even since the 1990s – are becoming their own bosses. Some have ties with the government and were civil servants before, but most, especially the younger ones, come from pretty humble backgrounds.

Many started with nothing, or next to nothing, and it is the belief in upward mobility that has been the driving force.

Many of these new companies, especially internet companies, are organised like those in Silicon Valley. Money and ownership are not controlled only by a key founder: they are shared. For example, the e-commerce company Alibaba, whose initial public offering last month was the largest in US history, overnight helped more than 10,000 employees become yuan multi-millionaires. More importantly, it has created a platform for countless people in China and their small businesses to find a way to make a living that did not exist before. Alibaba is now run by people that are mostly in their 20s or 30s. Jack Ma, who is 50, considers himself “too old”. Pony Ma, of Tencent – owner of the popular WeChat messaging service – has said his biggest concern is falling behind in the understanding of the new generation of post-1990s consumers.

Young people in China are keen to try their own luck and they aspire to be the next Jack Ma, Pony Ma, or Robin Li, of Baidu, the mainland search engine. (They hold the top three places in Bloomberg’s list of China’s richest people this year; all began their businesses about 15 years ago).

China is by no means perfect; indeed, far from it. Many point to its one-party rule: some would call it an authoritarian regime, corruption is still rampant and state-owned enterprises continue to enjoy special privileges. Yet, the rapid rise of entrepreneurship and its impact on the rest of the country have shown that even in an imperfect situation, one can find ways to make it work. This is precisely what entrepreneurship is about. Xi said this was the era of the “Chinese Dream”.But it is more than a dream. It takes vision, passion, commitment, a willingness to accept ambiguity and risks, and a carefully crafted plan. Many young mainlanders understand it, or at least are taking action, while many in Hong Kong still don’t, and are stuck in a rut. The divide between Hong Kong and the mainland is not only physical, but, more importantly, it’s mental.

What can be done to help create upward mobility for Hong Kong’s young people? We believe it must start with the private sector. During the first internet era in the late 1990s, Hong Kong had a vibrant investor community and a number of entrepreneurs, too. After the internet bubble burst, these entrepreneurs disappeared, while on the mainland they (re-)emerged and just kept going, in spite of failures. Investors turned their attention to the mainland.

Today, angel and venture capital investors in the city want to know what good ideas young Hongkongers have. Our young people should utilise the China market, especially when information and ideas are not necessarily constrained by physical boundaries.

The government must support this, though it has a disappointing track record. Tung Chee-hwa had a promising vision and Professor Tien Chang-lin’s report on innovation and technology was good, but unfortunately, it failed on implementation; Donald Tsang Yam-kuen neglected this entire area. Leung Chun-ying’s initiative to re-establish the Science and Technology Bureau is a good one, but it needs to be a higher priority. Funding must be sufficient and bureaucratic red tape minimised.It should be aligned with all bureaus; everyone must see that creating new industries, jobs and small and medium-sized enterprises, and employing young graduates, is a top priority for Hong Kong. The government must work closely with the private sector to make it work.

Ultimately, young Hongkongers should strive to be the best at what they choose to do, building on their own capabilities and passion, and leveraging the China market. This is the best way to influence not only Hong Kong, but also the mainland.

We are proud that many young local athletes won medals at the recent Asian Games after many years of focused training efforts. We must do the same in the business sector and create new industries and new jobs, reignite hope for our young people, and channel their energy into creating that better future. It can be done.

Edward Tse is founder & CEO of Gao Feng Advisory Company, a global strategy and management consulting business with roots in Greater China. Sunny Cheng is an environmental technology consultant

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as The only wayis up